To establish robotic surgery as a clinical standard, the field must invest in next-gen training and build a flexible framework so it is well-placed to adapt to future innovations.

This was one of the key takeaways from a recent webinar hosted by the International Medical Robotics Academy (IMRA) in partnership with Surgery International.

The expert discussion highlighted the challenges and opportunities facing seasoned surgeons and young trainees in a fast-evolving field.

Surgeons from around the globe tuned in to the free-to-attend ‘Adaptive Training Solutions in Robotic Surgery’ to gain fresh insights into adaptive training solutions in robotic surgery.

The event provided a comprehensive exploration into the future of robotic surgery training and featured some leading voices in the field.

The panel discussed how adaptive training can bridge gaps in current surgical education frameworks, enhancing skill development for both novice and experienced robotic surgeons.

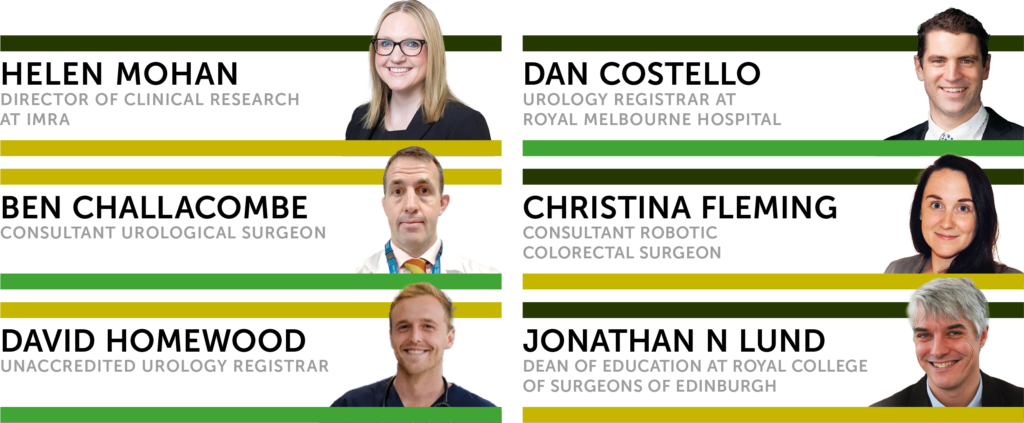

The moderator was Dr Helen Mohan, director of clinical research at the International Medical Robotics Academy and a colorectal surgeon at Peter McCallum Cancer Centre in Melbourne.

She emphasised the importance of evolving training methods to keep pace with rapid technological advancements.

‘Robotic surgery is transforming the medical landscape, and our approach to training must evolve with it. Adaptive training methods offer a practical path forward, making specialised skills more accessible to a broader range of healthcare professionals,’ she said.

A global line-up of surgical innovators each brought unique insights into adaptive training’s potential.

Dr Christina Fleming, a pioneering robotic colorectal surgeon from Limerick, Ireland, started the discussion. She offered an overview of the current landscape and emphasised the urgent need for robotic surgery training for surgical trainees as robotic procedures become more prevalent. She believes that despite high demand and interest among trainees, exposure to robotic training remains limited. She said this creates a ‘disconnect’ between training needs and what is being delivered in practice.

Urology specialists Dr Daniel Costello and Dr David Homewood shared emerging technologies, including virtual reality and 3D-printed organ models, that have the potential to simulate real-world scenarios more accurately than ever before.

Dr Homewood’s experience includes significant time assisting in robotic procedures, which has provided ‘excellent opportunities to understand the steps of a robotic operation’. He explained: ‘I’ve been fortunate to gain some experience at IMRA with simulation and simulated hydrogel models, which has given me more hands-on consult time in this area than many at my level. However, the general sentiment is that most people would like more operative consult time as part of their training. The challenge is finding the best and safest way to incorporate that. At a junior level, there’s likely more opportunity for assisting with robotic procedures than for other types of hands-on practice.’

Describing the challenges in robotics training for medical students and trainees, Dr Costello noted that while traditional training introduces basic surgical techniques early on, there’s a push to integrate robotics much sooner.

He explained that this year, the University of Melbourne launched a Robotics Discovery course that was so popular that it quickly oversubscribed, with five times the interest projected for next year.

‘This trend means that new interns may soon be more familiar with robotic technology than some of the consultants they work with, which may lead to eagerness but frustration when access to robotic hands-on experience is limited.’

The use of simulators for robotic surgery training is hindered by high costs and limited availability, often depending on hospital resources. Many simulators are attached to the da Vinci surgical robot, primarily used for live operations, making access incredibly challenging after hours or on weekends.

Although he hopes for more affordable and accessible simulation options, his team has also been developing synthetic organ models that can be transported to hospitals, potentially providing a viable solution.

Another issue arises when more advanced trainees with extensive simulator experience face difficulty progressing due to less-experienced consultants.

Dr Costello suggests that surgical training could benefit from modularised procedures. These procedures would allow trainees to gain recognised proficiencies in specific robotic skills, like anastomosis, so they can confidently take on actual procedural steps.

Dr Jonathan N Lund, an experienced educator, outgoing chair of the Joint Committee on Surgical Training (JCST) and soon-to-be Dean of Education at the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh, discussed adaptive learning frameworks that prioritise real-time feedback and peer collaboration, crucial for fostering a new generation of skilled robotic surgeons.

He noted that surgical training in the UK remains in crisis post-COVID, with recovery lagging and significant pressure from political demands to address waiting lists. Additionally, cases are increasingly shifted from NHS hospitals to hubs and private providers.

‘Access to robotic surgery is particularly challenging due to the consultant learning curve. Many consultants are keen to train on robotic systems, which excludes trainees and limits their opportunities. Data indicates that only about 800 robotic cases per month in the UK and Ireland involve trainees – roughly 1.75% of general surgeries and 3% of urology cases, where robotic surgery is more common.

This situation mirrors the early days of laparoscopic training; it wasn’t until a critical mass of consultants were trained that access improved.’

Advocating for a similar approach now, he suggests this will ensure training slots go to younger consultants and trainees who will use these skills long-term.

He added that robotic surgery faces additional challenges in equipment access and regional availability compared to laparoscopy. Despite some improvement, geographical disparities remain, which further restricts training access. Over 460 trainees are currently experiencing extended training periods, partly due to fewer available cases and the prolonged time consultants spend on each robotic case.

Robotic training will continue impacting trainees’ progression to CCT certification and readiness in robotic skills, he said.

Associate Professor Ben Challacombe, clinical lead for robotic surgery at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, discussed the value of virtual training environments, noting their role in reducing procedural risks while preparing trainees for complex surgeries.

He talked about the advantages of having access to eight robotic platforms across seven specialties, emphasising the long history of robotics since 2004. He highlighted the need for early and intensive training in robotic surgery, suggesting that a course called Robo Start could be a foundational programme for core trainees, allowing them to gain practical skills and certification. This initiative aims to prepare trainees to actively contribute in surgical settings by providing them with essential knowledge about robotic systems and procedures.

The discussion also touched upon the importance of collaboration among industry stakeholders, training institutions and healthcare providers to enhance robotic surgical training. However, the panel cautioned against training tied to specific robotic platforms so trainees can work across various systems, preventing limitations in future consultant positions.

Concluding the webinar, Dr Christina Fleming said: ‘Consultants, if we’re going to be utilising robotic surgery in our clinical practice, it is very important we ensure that we create training opportunities within that.

‘Robotics has been the biggest disruptor since laparoscopic surgery, but newer technologies and innovations will come into clinical practice much quicker. So getting it right with robotic surgery allows us to create an adaptable blueprint for future technologies.’